It’s the offseason, folks, and with the cadets out for summer military training, we don’t even have the preseason to talk about. Which is why we’re introducing a new series called “Army Football 101”. This series will serve as a basic primer for newcomers to Army Football fandom, and to that end, we’ll archive these articles in their own tab on our main page.

We start this series with Army’s offensive scheme, the triple-option.

Editor’s Note: With the release of EA Sports’ NCAA College Football 25 alongside the Army Team’s decision to go back to the Flexbone, we’re re-upping this article for a new generation.

The Flexbone

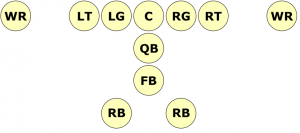

Theoretically, the triple-option is just a single play in an otherwise complicated run-based offensive scheme called the Flexbone. The Flexbone is a derivative of the old-school Wishbone offense, which featured a fullback and two running backs set in the backfield directly behind the quarterback.

The Wishbone (Wikipedia)

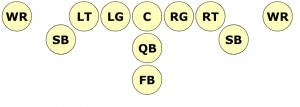

The Flexbone “flexes” these running backs out into the slot–the same slot to which NFL slot receivers go–giving the offense a higher degree of variability. Theoretically, the quarterback has an unprecedented a number of options: hand off to the fullback, pitch to either slotback, drop back and pass to either slotback, drop back and pass to one of the wide receivers, or keep the ball and run it himself. What’s more, because the formation is generally balanced, the play can go to either side. If the offense has superior speed, it will often run to the field side because that side offers more open space. However, if the team has superior discipline (like Army), it will often run to the short side of the field (the boundary), seeking an advantage in numbers through precision blocking. In military terms, this is not conceptually dissimilar to using Mass and Economy of Force to create a temporary numerical advantage at the decisive point of the play.

The Flexbone (Wikipedia)

The triple-option is Army Football’s base play out of the Flexbone. There are many ways to run it. Three common ways are up the Midline, outside using the Speed Option, or against the flow with the Counter. Under Head Coach Jeff Monken, Army tends to use the Midline Option the most. By contrast, Navy usually tries to get outside using variations of the Speed Option. Georgia Tech used to run variations of the Counter Option a lot under Head Coach Paul Johnson, but no one uses it so much that we would consider it their staple play.

The Fullback Dive

Every television broadcaster notes of Army, “It all starts with the fullback.” To put that in military terms, the Fullback Dive is the fixing attack that sets up the rest of the offense. As such, its fundamental job is to hold the defense in place in the middle of the field. This does not mean that the Fullback Dive is not supposed to work. In fact, it’s a good thing when one’s fixing attack gets penetration. However, the Fullback Dive is perhaps the least likely aspect of the triple-option to result in an explosive offensive play. Its success facilitates the rest of the offense.

The Fullback Dive works because it happens quickly. The quarterback starts under center, takes the snap, and hands to the fullback, who is immediately behind him. The fullback starts with the ball at most two yards behind the line of scrimmage. He plunges forward, picking up whatever yardage he can. At the same time, the offensive line plunges forward, cut-blocking to try to get defensive linemen to the ground and open running lanes in the middle of the field. When run correctly, the fullback can gain three or four yards before the defense even realizes that who has the ball.

Oddly, the Fullback Dive is often most effective against Power 5 teams. Because Power 5 players are all trying to get into the NFL, which is a passing league, so Power 5 defense tends to be about trying to get to the quarterback. Power 5 defensive linemen are therefore trying to get up-field, hit quarterbacks, and blow up plays. This is what will get them drafted.

This is also what gets them beat against the Fullback Dive. They’re looking at the quarterback, trying to get up-field, and then the play is in their laps and running past them. Against the Fullback Dive, a wrong first-step will turn a two or three yard run into a five or seven yard run.

The Quarterback Keeper

The quarterback reads the defense. If the defensive tackle is keyed on the fullback, or if the blocking just isn’t good, the quarterback pulls the ball, faking the hand-off. In the Midline Option, he then follows the fullback through the hole in the center of the line.

Ahmad Bradshaw’s ability to read defenses and run inside is what made him such a great quarterback at Army. Army ran versions of the Midline Option continuously with Bradshaw. The Black Knights’ final drive against San Diego State in the 2017 Armed Forces Bowl was an absolute clinic in the Midline Option. Bradshaw and the fullbacks ran right at the Aztecs’ defense, and yet the Aztecs still seemed to have no idea what was hitting them. After 40+ minutes on the field, their defense was physically unable to defend all of the potential options and variations.

However, the Midline is not the only way to run the option. If the quarterback pulls the ball and tries to get outside, the play becomes a version of the Speed Option. QB Kelvin Hopkins is perhaps a little more apt to run the Speed Option than was Bradshaw. Hopkins is a decidedly more versatile quarterback, but he’s maybe not quite as strong an inside runner. His ability to throw and pitch accurately on the run, however, make him much harder to defend in space.

The Speed Option is conceptually uncomplicated. If the defender plays the quarterback, the quarterback pitches outside to the slotback. If the defender cheats and tries to play the pitch, or if he’s just a step too slow, the quarterback turns up-field and takes what he can get. The clip below is great because we can see where the pitch would have gone–and therefore why keeping the ball was the correct decision.

It’s worth noting that the Flexbone allows for designed quarterback runs that don’t necessarily rely on fakes to the fullback and/or option-pitches. These straight power runs with the quarterback, i.e. Quarterback Power runs, are not at all uncommon in Army’s offense. In fact, all of the service academies–and quite a few other college teams–run Quarterback Power. But telling what’s a designed quarterback run, what’s a designed fullback run, and what’s actually a true Option play can be functionally impossible without hearing the offensive play-calls, especially from the sidelines or the broadcast television view of the game. Nevertheless, understanding the basic scheme enhances the game-day experience immeasurably.

The Option Pitch

The third leg of the triple-option is the Option Pitch. It’s rare off the Midline because 1) Army’s blocking tends to be good, so quarterbacks usually have a lane for the Quarterback Keeper, and 2) the Midline Triple-Option pitch typically occurs deep behind the line of scrimmage, allowing for the possibility of a big negative yardage play. Coach Monken hates negative plays. However, if the quarterback reads keep and then gets a defender in his face, he can pitch straight back to the slotback off the Midline. The upside is that the defense has usually over-committed, meaning that the slotback will have plenty of room to run if he can get outside.

The Midline Triple-Option is typically most useful when pressure is getting to the quarterback. Once the defensive end has committed, he’s virtually guaranteed that the slotback will get a step on the rest of the defense. Granted, that’s not always the way you’d draw it up. Still, if the slotback can get to the corner, the results are usually pretty good.

With all of that said, we tend to think of the Option-Pitch as coming off some version of the Speed-Option to the outside. There are many ways to set this up, but generally, the quarterback draws the defender in and then pitches laterally, hitting the slotback in stride. Because the defense has committed to the quarterback, the slotback has room to run. Because the quarterback hits the slotback in stride, the slotback is already moving at close to full speed when he gets the ball. The Speed-Option Pitch is therefore the most likely facet of the triple-option to become an explosive play.

In military terms, we might think of the Option Pitch as the envelopment to the Fullback Dive’s fixing attack.

Counter Option

The Counter-Option is mostly a tendency breaker. The quarterback fakes to the fullback, takes a step towards the play, and then reverses field, running back against (most) of the blocking action. A guard typically pulls and blocks, and the leading slotback on the counter side also blocks, but the play relies on getting most of the defense flowing away from the action because of the initial blocking. After the counter, the quarterback has the option to pitch or keep.

This example is a Quarterback Keeper:

The Rocket Sweep

The Rocket Sweep isn’t technically a play off of the triple-option. It’s a tendency breaking outside run set up by successful iterations of plays off the Midline. The Midline-Option forces the defense inside to guard against the Fullback Dive and the Quarterback Follow, so a toss to a speedy slotback running outside tends to catch defenses wrong-footed. The leading slotback blocks, setting up a toss to the trailing slotback, who has to get outside and make something happen.

When the rest of the offense is working, this play is a thing of beauty.