Some rivalries define eras. Nebraska-Oklahoma defined the 1970s, and Florida State-Miami defined the 1980s. Army had their own decade-defining rivalry through their clashes with Notre Dame in the 1940s, but another rivalry arguably carries more importance to the history and progress of college football — Army-Syracuse.

That may sound strange considering that Syracuse and Army will meet for only the 22nd time this Saturday. Even though both fanbases are thrilled for the first of a four-game renewal of this Empire State rivalry, few fans from either school recognize the past importance this series had.

The rivalry did not pick up until 1956 when Syracuse hosted Army at Archbold Stadium for the first meeting between the two in 30 years. Starting for the Syracuse Orange was a young back named Jim Brown. Brown’s steady 125-yard performance paced the Orange to a 7-0 victory as Syracuse capped 1956 with a Cotton Bowl appearance.

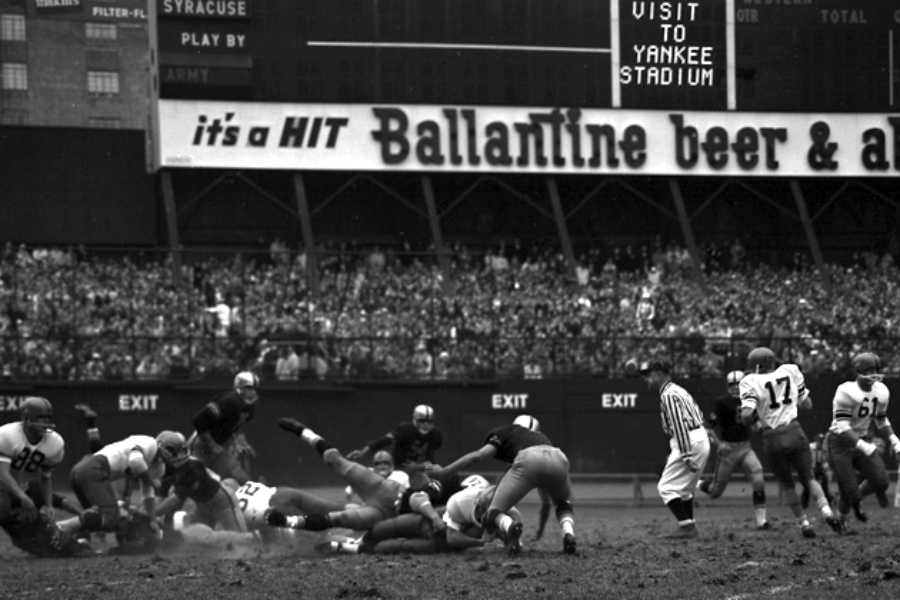

Four years later, Army faced another great Syracuse back, Ernie Davis, as the Orange were defending national champions. This time, the setting was Yankee Stadium. Syracuse became yet another program attempting to fill the void Notre Dame left as Army’s perennial Yankee Stadium opponent. Davis, a future Heisman Trophy winner, dazzled the Bronx crowd with 11 carries for 110 yards and an interception, but it was not enough. Army prevailed 9-6.

Army’s 1960s games with Syracuse represent two key turning points in college football — the beginning of the end of service academy football’s dominance and the widespread integration of college football.

Army played Syracuse twice more in New York City ballparks in the 1960s, winning 9-2 at the Polo Grounds in 1962 and losing 27-15 at Yankee Stadium in 1964. Alas, those final two games were just feeble attempts at maintaining the rich tradition of Army football in the Big Apple. Poor attendance marred both games. Only 29,000 showed up to the crumbling Polo Grounds in ‘62 while 37,552 flocked to Yankee Stadium two years later for Army’s penultimate game at the old ballpark.

From that point forward, service academy teams contending for national titles became a rarity as the NFL increased in popularity alongside the ongoing reality of the Vietnam War. Lucrative contracts resulting from the AFL-NFL bidding war and souring national opinions of Vietnam made playing football at Army and Navy less alluring to top recruits.

More importantly, Black players played crucial roles against Army at a time when its football team had not yet integrated. Contrary to popular belief (but corroborated through page 34 of my Senior thesis), Army had not integrated until 1964 when Bobby Whaley was a member of the Freshman team. Two years later, Gary Steele became the first Black starter on the football team and is widely recognized as Army’s first Black player.

It is reasonable to believe that Jim Brown and Ernie Davis’ performances against Army convinced West Point of the utility of integrating the football program. The final straw may have been when future AFL legends Floyd Little and Jim Nance combined for 168 yards and all four of Syracuse’s touchdowns in the 1964 game.

Saturday’s Army-Syracuse game may seem like just another Northeast rivalry lost in the winds of conference realignment, but it is also so much more than that. Army and Syracuse are two programs from college football’s Old Guard. They represent the golden age of college football and its transformation to both a professional game and a game that broke racial barriers.