This is the fifth entry into the Army Football 101 series. If you missed any of the previous entries, they are archived below:

Army Football 101: The Triple-Option

Army Football 101: Defense

As For Football’s Guide to Michie Stadium

5 Traditions that Make Army Football Great

Emblem Athletic Sponsors As For Football

We’ll wrap the series next week with a look back at Army vs. Rice (2016). If you want to get a jump on things, this link will take you to an archived YouTube video of the game. Watch it now to get prepared for the discussion.

MacArthur’s Message, via Bugle Notes.

The idea for this week’s article came last year. I posted a question to my social media networks: “Thinking about doing one more Army Football season preview post. I’ve got a couple of topics. What else would you like to see?”

To say the very least, I was surprised by some of the answers.

I got a question about Army’s then-revamped Offensive Line, which wasn’t a huge surprise. Some folks wondered as well whether emergent starting QB Kelvin Hopkins was up to the task. But most of the responses fell in line with this one, which came from my classmate and good friend Ray, currently a permanent professor of History at the Academy:

“What should athletic experience be contributing to the development of future officers? Why (besides $) do we put all this effort into a relatively small chunk of cadet life?”

I wasn’t sure where to go with that. I’m not convinced that my five years in uniform make me an expert on the officer training goals of the United States Military Academy. Honestly, I get a little nervous writing about the actual military side of West Point because I have so many friends who did so much more in the Army. I liked the Army but didn’t love it. That’s never been a secret.

But my friends can be pretty insistent, and I’ll own that I have about as much Corps Squad experience as anybody, and that I’ve always felt like I benefited from that experience as much as anyone. Maybe more importantly, I wouldn’t say that my experiences swimming at Army were “a relatively small chunk of [my] cadet life”. For me, swimming at Army felt like an all-consuming passion that eclipsed everything in my life for four solid years. The lessons that I learned in the pool were the most important lessons I learned at West Point. Those are the ones that stuck with me.

So sure, I thought. I can talk about that.

But then another friend followed up privately with something that was decidedly more provocative:

“I would focus on teamwork and building a winning culture. We haven’t won a war since 1945. Instilling the importance of achieving victory was one of the cornerstones of the former Supe’s vision. It wasn’t just about beating Navy. It was about giving every ounce of your effort to WIN.”

The thing you have to realize—that I sometimes forget—is that my friends are all senior field grade officers now, that they’ve now been in uniform for more than twenty-five years, and that they are deeply, emotionally invested in the real culture of the United States Army.

They own it. They live it every day.

For guys like that, the War in Afghanistan isn’t something that’s happening on television. Nor are they simply waxing poetic about their alma mater’s football team. Rather, the distribution of cadet time and resources are a legitimate concern, especially given our national security realities and the inescapable fact that we live in a resource-constrained environment across myriad governmental functions but most particularly as it comes to soldier training time. I personally take issue with my friend’s assertion that we haven’t won a war since 1945*, but he’s right that the Army itself can’t afford to field a sports team with a defeatist attitude. It’s not a great sign that we suffered through a full generation of leaders at West Point who seemed okay with athletic mediocrity. If these guys will accept mediocrity in football, then they’ll accept it everywhere. I mean, that’s a bad look, right?

MacArthur’s statue, via Wikipedia.

Winning on the football field is a lot clearer-cut than is winning the hearts and minds of the Afghani people. But still, as they say, there is no substitute for victory. GEN Colin Powell articulated this clearly in the Powell Doctrine in the wake of Vietnam. He and his peers lost a war and then reformed the Army out of almost nothing back in the 1970s, with the fruits coming in Berlin in 1989 and in Kuwait in 1991. That, to me, is what winning looks like for the Army. Task and purpose, without moving the goalposts after kickoff. By contrast, today’s leaders have oftentimes seemed a little too willing to just sort of go along to get along. The problems that our nation faces just seem too big. Leaders have shown a decided willingness to throw their hands in the air. “Who could have known how complicated this would be?”

It’s not good enough. That is not what winning looks like.

I guess what I learned by swimming—at Army—is that there are times when folks are counting on you when you simply cannot fail. There are times when your teammates are looking for you to make a play, and you just have to rise to the occasion and make it. Circumstances don’t matter, nor do excuses. The version of you that doesn’t crack under pressure, that’s getting through this, that fights and wins… You have to be that guy when that’s the guy that your teammates need. The times when I’ve been my best self, when I’ve transcended what I thought were my physical limitations and come up with legitimately peak performances, those have mostly come in these kinds of situations. Learning to channel that, to get to the other side without breaking, to not just hit the wall but to smash it fearlessly, that’s the work of a lifetime.

Men and women don’t just fight and win because they’re ornery. They have to learn the commitment that it takes to be truly outstanding.

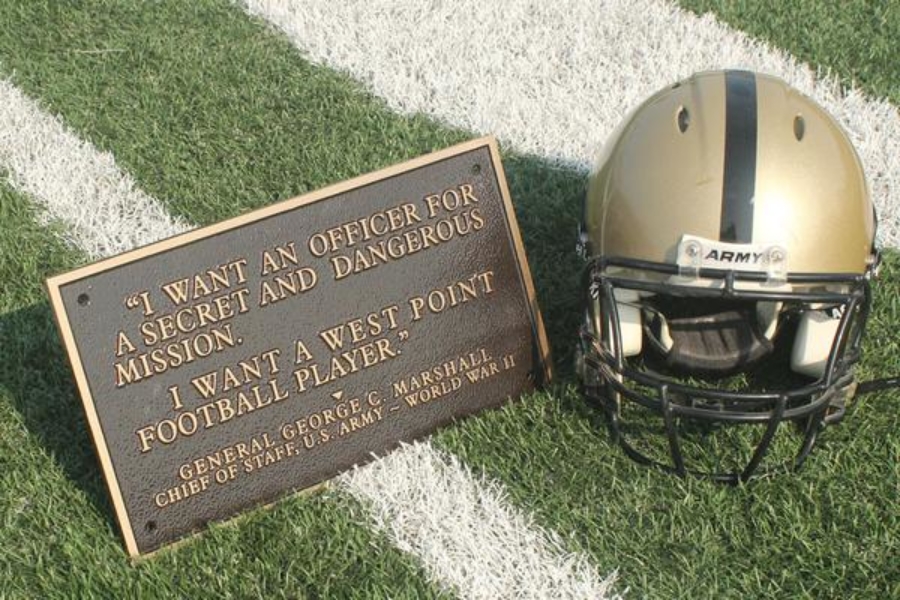

Determination, toughness and winning led to this day.

Thank you @POTUS for hosting us at the @WhiteHouse to celebrate our CIC ? title.#GoArmy pic.twitter.com/nNUW7P0zKl

— Army Football (@ArmyWP_Football) May 6, 2019

The hardest thing I did at West Point was a set of 5 x 300 fly on something like 3:30. We did it cow year. Coach Ray Bosse put me in with the distance swimmers and had me swim their set, but butterfly. It was 5 x 300, and it was—by a lot—the most transcendentally difficult thing I’ve ever done in my entire life. I don’t know how to describe it except to say that at a certain point my mind kind of shut down, and I became one with the struggle. Like I was ramming my head into a wall, and eventually the wall somehow gave way. But there was another wall after that first one, so I went at that one head-first, too. And then that one fell, but there was another behind it. So I went at that one, relentlessly. On and on. That’s what it was like.

I had to attack fearlessly just to keep up, so that’s what I did. And it was amazing, like, “I am bashing these walls down with my face!”

I went to the National Training Center as a tank platoon leader a few years later, and I was awake for four days. We did a movement-to-contact, followed by a deliberate defense, followed by a hasty attack, and I somehow never got a chance to lay down over the entirety of that time. And it was exactly the same. Not coincidentally, the First Gulf War was one hundred hours, i.e. exactly four days, and I’ve talked to a lot of people about it, and they’ll tell you that this was one of the hardest parts—moving forward relentlessly in the attack for four days. But that was what victory looked like. That was getting to the other side.

None of which means that I got some special “victory sauce” by being a corps squad athlete. That’s definitely not what happened. The Academy tests different people in different ways, and everybody’s got their own stories. No one can do everything well; that’s what makes it such a compelling experience. Rather, I think the point my friend was trying to make was that it’s about the expectation. If you expect to win, if you believe that you can win, and you’re fully committed to winning, then you’ll push yourself further and achieve more, and that’s how you actually get to the other side and win. By contrast, if you accept defeat, and you compromise and tell yourself that it’s okay because you tried your best, well, that’s how you fail. True commitment goes all in, with no reserve. That belief in oneself–in victory–is an essential component. When they say, “You have to want it more,” that’s not rhetorical. High end athletics is a test of commitment.

“It’s connected me with a lot of really important people in my life who've kind of transformed me and changed me and kind of pushed me to be what I can be. Everything I've done is kind of a reflection of their investment.” – Kenneth Brinson, @ArmyWP_Football pic.twitter.com/OkQUzanGFi

— Future For Football (@Future4Football) May 29, 2019

It’s no surprise that these are the terms in which Coach Monken talks. You look at what these guys are doing, and it’s about commitment. It’s about brotherhood. This follows a basic rule of leadership. Soldiers may fail themselves, but they rarely fail their buddies. The commitment that these guys have, to fight harder–for each other–to achieve goals that they believe they can get together, that’s powerful stuff. It is no surprise that it’s working.

As my buddy said, the Regular Army needs that, and here we are.

* * *

* The Republic of Korea is a going concern today because of the success of American arms in 1951. Also, the U.S. won decisively in Grenada, Panama, and in the Gulf in 1991.